The scale of the problem:

Trafficking women and girls for the purposes of sexual exploitation is a modern, global form of slavery. In 2007, the Immigrant Council of Ireland commissioned research designed to map the scale of Ireland’s sex industry and to uncover the scale of exploitation of women and girls.

The resulting report, ‘Globalisation, Sex Trafficking and Prostitution: the Experiences of Migrant Women in Ireland’ (Kelleher, Pillinger and O’Connor, 2009), uncovered the shocking reality of rape, abuse and sexual exploitation of victims of sex trafficking. It documents the physical, emotional and psychological harm these women and girls suffered. The report was based on interviews with women and the examination of data and information from service providers. It revealed that, over a 21-month period from 2007 to 2008, 102 women and girls who were victims of trafficking presented at services. (This used the internationally-agreed definition of victims of trafficking.) Of these, 11 were children at the time they were trafficked. We also know that these are a fraction of the real number of victims of trafficking in this country. These are the ones who were rescued or escaped from their traffickers and pimps.

The resulting report, ‘Globalisation, Sex Trafficking and Prostitution: the Experiences of Migrant Women in Ireland’ (Kelleher, Pillinger and O’Connor, 2009), uncovered the shocking reality of rape, abuse and sexual exploitation of victims of sex trafficking. It documents the physical, emotional and psychological harm these women and girls suffered. The report was based on interviews with women and the examination of data and information from service providers. It revealed that, over a 21-month period from 2007 to 2008, 102 women and girls who were victims of trafficking presented at services. (This used the internationally-agreed definition of victims of trafficking.) Of these, 11 were children at the time they were trafficked. We also know that these are a fraction of the real number of victims of trafficking in this country. These are the ones who were rescued or escaped from their traffickers and pimps.

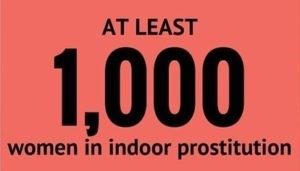

The sex industry in Ireland has undergone significant changes in recent times. It has moved off the streets and into apartments and houses. The research estimates that between 800 and 1,000 women are in the indoor commercial sex trade controlled by organised crime. Men now access prostitution via the internet or their mobile phones. The research highlights the fact that there is no clear line between those who are trafficked and those who “consent” to become involved in the sex industry. Many of the women involved in Ireland’s sex industry, even those who do not meet the definition of a victim of trafficking, have had no real choice: poverty, deception and gross exploitation mark many of their stories. The demand from men who buy sex fuels both the trade in trafficked women and girls, and sustains a prostitution industry worth an estimated €180 million a year in Ireland.

The solution:

Effectively tackling sex trafficking in Ireland will require a response to deal with demand from men to buy sex. The sex industry, which exploits and harms women, exists because there is a demand from men to buy sex. The alliance is therefore calling on the Irish Government to learn from those countries that have established good practice for dealing with sex trafficking. Among the countries that penalise the purchase of sex are Sweden, Norway, Iceland and Northern Ireland. Those countries have legislated to penalise the purchase of sex, while decriminalising the selling of sex. Practice shows that this approach reduces demand for prostitution and incidences of trafficking for sexual exploitation.

The law in Sweden was introduced in 1999 in response to concern that prostitution constitutes violence against women and is incompatible with gender equality. The law imposes penalties on buyers of sex but decriminalises sellers of sex. The law is regarded as not just punitive, but also declarative and normative in relation to challenging the sexual exploitation of girls and women and promoting the wider goal of gender equality. The law enjoys consistently high public support in Sweden, with surveys indicating that more than 70% favour the measures. The legislation recently underwent a 10-year evaluation, which found a reduction in the number of men paying for sex, a reduction in the number of women involved in prostitution, and a dramatic reduction in the numbers of women and girls trafficked to Sweden for the purposes of sexual exploitation. The shrinking commercial sex industry in Sweden impacted on the level of sex trafficking in adjacent countries, resulting in Norway and Iceland deciding to replicate the Swedish legislation in recognition of its merits.

The law in Sweden was introduced in 1999 in response to concern that prostitution constitutes violence against women and is incompatible with gender equality. The law imposes penalties on buyers of sex but decriminalises sellers of sex. The law is regarded as not just punitive, but also declarative and normative in relation to challenging the sexual exploitation of girls and women and promoting the wider goal of gender equality. The law enjoys consistently high public support in Sweden, with surveys indicating that more than 70% favour the measures. The legislation recently underwent a 10-year evaluation, which found a reduction in the number of men paying for sex, a reduction in the number of women involved in prostitution, and a dramatic reduction in the numbers of women and girls trafficked to Sweden for the purposes of sexual exploitation. The shrinking commercial sex industry in Sweden impacted on the level of sex trafficking in adjacent countries, resulting in Norway and Iceland deciding to replicate the Swedish legislation in recognition of its merits.

The situation in Ireland:

Buying sex is not illegal in Ireland, nor is selling sexual services. The law protects these transactions as agreements between consenting adults. Some activities associated with prostitution are outlawed, however, as public order offences. These include curb-crawling, soliciting in public, loitering in public places, brothel-keeping and living off immoral earnings. While it is illegal to have sex with someone younger than 17, the courts have ruled that being mistaken about the age of the young person may be used as a defence. In 2008, it became illegal to buy sex from someone who had been trafficked. This was done through the Criminal Justice (Human Trafficking) Act 2008. Section 5 of the Act provides for penalties for people who buy sex from a‘trafficked person’. However, a‘trafficked person ’is defined as ‘a person in respect of whom a trafficking crime has been committed’, and there is concern that this may be interpreted as requiring a conviction of a person for the trafficking offence before somebody could be prosecuted for buying sex from the trafficked person. Also, the Act does not provide for ‘strict liability’. This means that the purchaser of sex can use the defence that he did not know that the person from whom he was purchasing sex had been trafficked.

Buying sex is not illegal in Ireland, nor is selling sexual services. The law protects these transactions as agreements between consenting adults. Some activities associated with prostitution are outlawed, however, as public order offences. These include curb-crawling, soliciting in public, loitering in public places, brothel-keeping and living off immoral earnings. While it is illegal to have sex with someone younger than 17, the courts have ruled that being mistaken about the age of the young person may be used as a defence. In 2008, it became illegal to buy sex from someone who had been trafficked. This was done through the Criminal Justice (Human Trafficking) Act 2008. Section 5 of the Act provides for penalties for people who buy sex from a‘trafficked person’. However, a‘trafficked person ’is defined as ‘a person in respect of whom a trafficking crime has been committed’, and there is concern that this may be interpreted as requiring a conviction of a person for the trafficking offence before somebody could be prosecuted for buying sex from the trafficked person. Also, the Act does not provide for ‘strict liability’. This means that the purchaser of sex can use the defence that he did not know that the person from whom he was purchasing sex had been trafficked.

In 2015, the Government published the Sexual Offences Bill, which introduces sex buyer laws and provisions to offer protections to those exploited in the Sex Trade. The Sexual Offences Bill finished its journey through the Seanad, passing with cross-party support. It then entered Second Stage in the Dáil, the first of three stages before the Bill can be enacted. Statements of support for the Bill were made by all four leading political parties. As it stands the Bill includes laws to criminalise the purchase of sex, while explicitly decriminalising the sale of sex.

Denise Charlton, Chair of the Turn Off the Red Light campaign, explains the growing international support for Irish law-makers to tackle the demand for prostitution: